On September 19, Baja California Governor Jaime Bonilla signed into law the establishment of the 169-acre Arroyo San Miguel State Park, just north of Ensenada. The new park, the first state park in the history of Baja California, includes the beach at the famed San Miguel river mouth, a cobblestone point, as well as the riparian watershed of the same name.

“The San Miguel break, which was the first place where surfing began in Mexico, is an iconic site for the surfing community, so we celebrate this decree,” said Eduardo Echegaray, president of the Baja California Surfing Association.

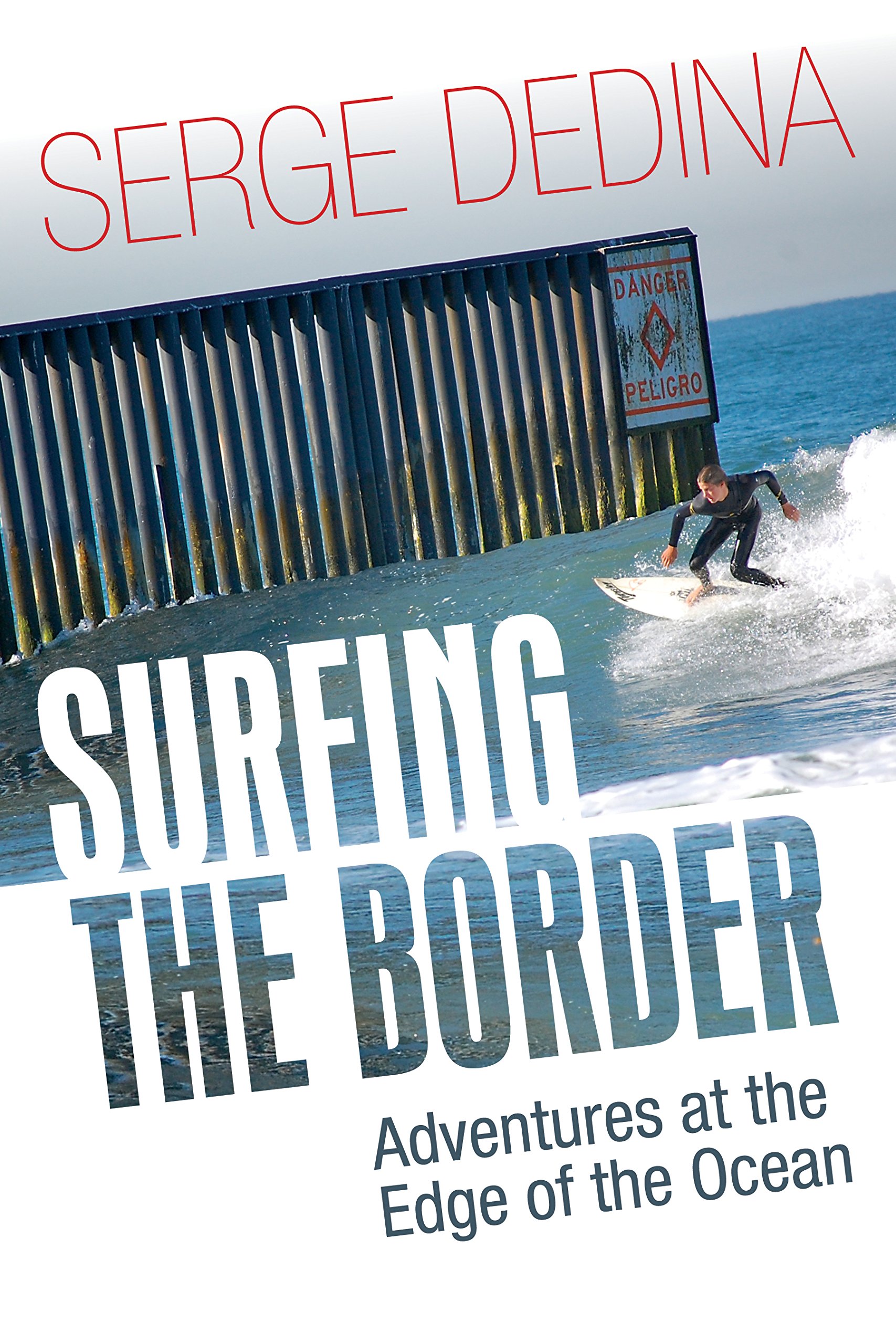

Daniel Dedina enjoys an early winter session at San Miguel. Photo: WILDCOAST

The new state park helps to strengthen the Bahia de Todos Santos World Surfing Reserve that includes San Miguel, Todos Santos Island, and Salsipuedes among other surf breaks. The reserve proposal was supported by a coalition of organizations including Pronatura-Noroeste, Save the Waves, Northwest Environmental Law Center (DAN), Pro Esteros, Island Conservation Group (GECI)and WILDCOAST.

“With this decree, Governor Bonilla has left a legacy for the people of Baja California, and in particular Ensenada,” said Gustavo Danemann, executive director of Pronatura Noroeste. “The Arroyo San Miguel State Park is the first natural protected area to be established under state jurisdiction, and with this, it sets a precedent on the vision we have in Baja California for the protection and public and sustainable use of our landscapes and natural areas.”

Similar to the San Mateo Creek watershed within San Onofre State Beach, Arroyo San Miguel State Park is a classic riparian oak watershed – a vibrant coastal and terrestrial ecosystem as well as a fabled surf spot.

“Arroyo San Miguel State Park is dominated by riparian habitats with oaks, willows and reeds as well as species of native vegetation, especially increasingly threatened coastal sage scrub,” said WILDCOAST Mexico director Mónica Franco. “It is also home to resident and migratory birds such as quail and peregrine falcons.”

The most important element for surfers is that it restricts development along the shoreline and along the western end of the watershed and is a big victory for the environmental and surfing community of Baja California.

“The designation of the Arroyo San Miguel State Park is a truly community initiative,” said Danemann. “The Baja California government demonstrated fundamental support and commitment to make this possible. We are confident that the new state administration will also support the conservation of the Arroyo San Miguel State Park, and we reaffirm our commitment to continue collaborating in this project.”

Community cleanup prior to a surf contest at Arroyo San Miguel State Park, Baja California, Mexico. The Ensenada surf and environmental community have been very involved in the development of the state park and the protection of the surf break, wetland, and watershed. Photo: WILDCOAST

Originally published in The Inertia.

During the nesting season, 100,000 olive ridley sea turtles can arrive at Playa Morro Ayuta in Oaxaca to lay their eggs in a single day. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB

During the nesting season, 100,000 olive ridley sea turtles can arrive at Playa Morro Ayuta in Oaxaca to lay their eggs in a single day. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB Birds of a feather taking advantage of their natural feeding grounds. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB

Birds of a feather taking advantage of their natural feeding grounds. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB The coral reefs of nearby Huatulco National Park are among the most well preserved in southern Mexico. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB

The coral reefs of nearby Huatulco National Park are among the most well preserved in southern Mexico. – CLAUDIO CONTRERAS KOOB The watersheds and tropical forests in the mountains above Barra de la Cruz and Huatulco, Oaxaca help to store water and atmospheric carbon and are critical in the fight against climate change. – MIGUEL ANGEL DE LA CUEVA

The watersheds and tropical forests in the mountains above Barra de la Cruz and Huatulco, Oaxaca help to store water and atmospheric carbon and are critical in the fight against climate change. – MIGUEL ANGEL DE LA CUEVA